Steven J Courtney, Helen M Gunter, and Steven Jones

In this response to Saunders (2021), we have been galvanised as much by his misuse of genetic evidence as by the claims that derive from it.

We intend here to focus on the former, but use specific examples from his seven claims to demonstrate how this misuse serves only to maintain the status quo.

We use the metaphor of conjured fabrications to shed light on the way in which this misuse is integral to conservative modes of social reproduction and draws on recognisable tropes, all illusory and, paradoxically in this genetics-steeped discourse, all profoundly sociological.

The promotion and defence of private education tends to be located in ideological claims about libertarian freedom as a personal and family property, where the segregation of children into different school types is further justified on the basis of an assumed causal relationship between the entitlements of family resources (e.g. money, status, networks) and the ability of offspring.

For example, Tooley presents the validity and vitality of the privacy within and for the private both through ridiculing democratic processes and conduct (Tooley 1995), and by arguing for the “3Fs” of “family, freedom and philanthropy” (Tooley 2000: 220).

Such arguments are replete with conjured fabrications whereby normative trickery is invoked to make claims about the world as it is and what it could be through the acceptance of ideological positioning – those who do not have the resources to attend private schools have to accept marketized inequity (see Courtney 2021; Courtney and Gunter 2020).

Magic tricks are vital because the exceptionalism that underpins private education is not only contra democracy but also increasingly dangerous to democratic values and processes (e.g. Green and Kynaston 2019). The question to be addressed is: why can’t all children be educated together in their local school? (Ryan 2019).

Contrarian sociologist Saunders conjures up his ideological defence of the segregation of children by deploying genetics: “The main reason pupils from private schools out-perform those from non-selective state schools in university entry is that they are, on average, brighter”, and he then goes on to state: “Robert Plomin’s research confirms this”.

Such a claim exposes the trickery in two main ways: first, Plomin’s work cannot be used to justify private schools; and second, Plomin’s work has been subjected to significant methodological critiques.

Saunders is wrong to use Plomin’s work to justify selection and access to school places.

Plomin (2018) does argue that: “children in private and grammar schools in the UK have substantially higher education attainment polygenic scores than students in comprehensive schools” (172), and he goes on to explain that this is because private schools select children, where in fact, “students would have done as well if they had not gone to private schools” (173).

This has been demonstrated through the evidence against academic selection at 11 (Gorard and Siddiqui 2018), and the adoption of the common school, where in Finland all children attend high-quality local schools, and the children from families of different economic resources not only achieve excellent examination outcomes, but also learn to respect each other (Sahlberg 2015).

In fact, for Plomin, the biggest learning outcome from his work is that access to a school place should not be based on selection, and instead the common school can be a “genetically sensitive school” where “every child of every faith, every race, and every social background will want to be educated there” (Asbury and Plomin 2014: 178-179).

Plomin’s argument is that use of genetic data would mean that teachers could accurately predict children’s learning needs, and so plan and deliver a personalised learning programme without segregating children into separate classes or schools or communities.

Saunders is wrong to use Plomin’s work to predict the abilities of children in private schools without engaging in the debates over methodology (e.g. Dorling 2015; 2019; Gillborn 2016; Mithen 2018). If there is a blueprint in an individual human it may be a factor but it does not determine who ‘I’ actually turn out to be.

Ball (2018) argues that Plomin is focused on the “difference between individuals, not to individuals” (60, original emphasis). What happens to each individual during a lifetime is important because “we don’t all have a shared ‘given situation’ – we each have a distinct life” (61).

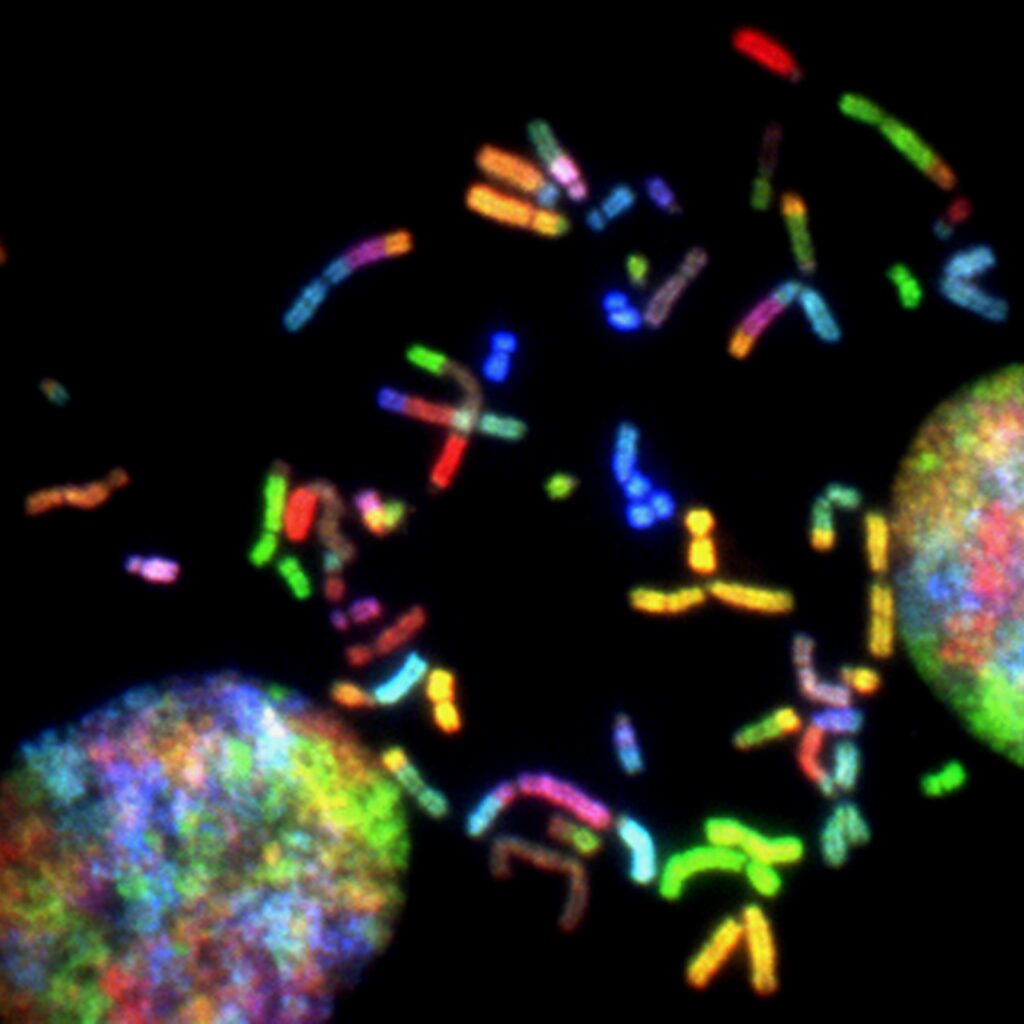

It seems that genes are part of who we are but do not define who we are, and importantly Saunders needs to read up on epigenetics in general (Meloni 2019) and in education (Youdell and Lindley 2019).

Perhaps parents who pay fees for private education actually do understand the impact of structural power (class, taste, family name) on the life chances of their children, and while they may engage with the conceit of genetic superiority, in reality they are buying into an experience that will structure the agency of their child, and importantly the agency of those who will engage with their child during their life course.

This challenges Plomin’s genetically sensitive approach to personalization, because what really matters is how the person with the genes is characterized and categorized as a power structure that generates advantage and disadvantage.

Conjured fabrications are replete in Saunders’ defence of private education. The social mobility ‘truths’ that he peddles are dependent on the premise that middle-class children inherit superior DNA.

This enables Saunders to admit that middle-class children are indeed twice as likely to get middle-class jobs than working-class children, but simultaneously to deny that this is due to class privileges.

Saunders similarly argues that we should not be surprised that top universities appear to have an over-representation of private-school entrants because “after all, these kids generally have very successful parents”.

The familiar discursive move is then made of implying that this is a “truth” which cannot be acknowledged, presumably because Leftist educationalists are too blinded by their prejudices.

Fabrications about “innate ability” are also reproduced through Saunders’ simplistic understandings of IQ tests. Such tests are culturally biased, and intelligence is not the linear, immutable and objectively measurable quality that Saunders mistakes it for.

Differences in IQ scores are unproblematically assumed to be an explanation for varying outcomes, rather than the consequences of access to varying educational resources.

In the comments beneath one of his pieces, Saunders responds to his critics by asking “Do people really think that achievement in life has nothing to do with cognitive ability?” This is a ‘straw man’ argument – few would deny any link at all.

Similarly, Saunders’ faith in meritocracy is largely based on the claim that there is some social mobility in the UK (which, again, few would deny). The problem is that from this Saunders concludes that society should accept the status quo, including the persistent over-representation of private-school students in elite universities and in elite professions.

This is a problematic leap, particularly troubling because of the misappropriations of genetic studies to confer a sense of scientific legitimacy to old and reactionary arguments.

The conjured fabrications do no more than represent Saunders’ ideological positioning; substantively, absent the genetics fluff, they are the same bunny being pulled from the same hat that we’ve seen many times before.

Importantly, they offer no explanation as to why children cannot be educated together in their local school.

Steven J Courtney, Helen M Gunter, and Steven Jones are academics at the Manchester Institute of Education, University of Manchester