Author:

Richard Beard

Reviewed by:

Sam Delaney

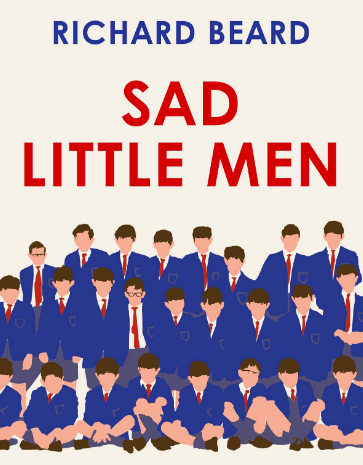

In Sad Little Men: Private Schools and the Ruin of England, we learn that Richard Beard was sent off to boarding school when he was just eight years old.

(When I was eight I couldn’t spend a night at my nan’s without freaking out and crying for my mum. But anyway.)

So Beard went to a prep school called Pinewood followed by the public boarding school Radley College in Oxfordshire. He was good at sports, which helped, he says. That meant he was popular and swerved most of the bullying that went on.

Maybe at the time he actually convinced himself he really was having a good time. He certainly gave that impression in his letters home to his parents, extracts of which he includes in this book. ‘Dear Mummy and Daddy…thank you for sending me to Pinewood. It is very nice here. I am running out of sweeties, can you send me some more?’

Now in his fifties, Beard has done a great deal of reflecting on his childhood and concluded that he really hadn’t enjoyed his schooldays much at all.

He lists numerous ways in which it impacted negatively on his mental health, his emotional life and his perspective on the wider world. He’s a great writer and he paints a vivid picture of the often lonely, isolated, sad and confused life of a little boy who was effectively rejected by his own mum and dad when he barely knew how to tie his laces.

I felt genuinely sad for him throughout the book. Here was a nice lad, who forged a more sensitive personality than the one afforded by his often brutal education, through his passion for books.

Like many kids – not just the ones sent to boarding school – he had to spend a great deal of his early life pretending to be okay when he clearly wasn’t.

The letters home to his mum were designed to reassure her that she wasn’t really as cruel as she might have suspected. They were also, he says, supposed to demonstrate his appreciation and gratitude.

This is often the perverse dynamic that exists between kids and their parents. Most of us, irrespective of class or educational background, put far too much effort into reassuring our parents that they are loving us sufficiently, caring for us properly and giving to us generously.

Beard says that he, and many of the other boys who shared his predicament, did so simply as a plea for the love they craved so deeply while they were locked all alone in their chilly dorms, miles from home with only a peculiar and imposing ‘matron’ attending to their myriad emotional needs.

Mum and Dad were withholding love in one of the most profound ways possible; the natural reaction of a scared and rejected child was to just beg harder for it.

The mass gaslighting of children by their care-givers is a curious phenomenon that probably demands more attention. In Sad Little Men we get a pretty thorough and compelling case study.

Anyway, aside from Beard’s own experiences, this book seeks to draw broader conclusions about the impact public school culture has had on our society as a whole.

He is roughly the same age as David Cameron and Boris Johnson, the two figures who have loomed largest over the country for the past decade and a bit.

Beard’s central thesis is that the system Cameron and Johnson were raised in was custom-built to turn little boys into men of confidence, resilience and forcefulness. Or, to put it another way, arrogant bullies with little in the way of empathy.

Public schools isolated the children in a sort of netherworld – Beard says they were even cut off from the national news during term time.

This allowed the school authorities to totally hypnotise pupils into a cult mentality. They were taught to buy into an idea of British superiority and a warped, war-obsessed, jingoistic idea of history that – even in the late seventies – was madly outdated.

Back in the olden days, Britain needed men to run the Empire. An empathy deficit was considered a virtue in such men – because ruling colonies with an iron fist required a pretty brutal emotional disconnect with the human lives you were governing.

But decades after the Empire had crumbled, boys like Beard, Cameron and Johnson were still being trained to disregard all feelings – including their own. As Beard puts it:

“We were made afraid to feel foolish, angry, loving, stupid, sad, dependent, excited and demanding. We were wary of feeling full stop. Which meant that people not blessed with a private education were, compared to us, fizzing with emotions and therefore insufferably weak.”

This is the really chilling part of Beard’s polemic. Boys like him were explicitly instilled with a sense of sneering superiority towards anyone who wasn’t just like them (not just the lower orders, he says, but foreigners and women too).

He quotes the Molesworth books by Geoffrey Willians, in which the masters warn their silver-spoon students about ‘oiks’: “Take no notice of them Molesworth. They do not know any better.”

Certainly, it’s an attitude you can trace through government conduct over the past eleven years: from austerity, to Brexit to Covid, the public schoolboys at the top seem to have been both out of touch with and largely indifferent towards the feelings and experiences of ordinary folk.

Being able to make huge decisions that screw with millions of strangers’ lives while still being able to sleep at night is, after all, what they were trained to do. It’s what their parents paid for.

Beard points to the 1980 documentary series made at Radley College called Public School. In it, the headmaster states his aim as teaching ‘the right habits for life.’

As Beard points out, the sorts of habits widely associated with his generation of public schoolboys include wrecking Oxford restaurants, paying minimum wage, shifting profits offshore and accepting political appointments that they’re clearly unqualified for. It’s a convincing point.

This is a very angry book, yes. But it is also shrewd, sensitive and compelling. I found myself thinking that, once upon a time, public schools might have had a warped sort of practicality.

When Britain’s business model was dependent on constant war and exploitation, maybe we really did need a consistent flow of cold-hearted egotists to help run things.

But why would anyone send their child to a public school today? Academic outcome is just as dependent on the socio-economic circumstances and emotional environment pupils experience in the home as the school they go to.

So if it’s not exam results that drives parents to send their kids to these places, what is it? Fear, status-obsession or sheer bloody laziness? Take your pick.

Sam Delaney is a writer and broadcaster. His most recent book is Mad Men And Bad Men – What Happened When British Politics Met Advertising (Faber)