Will Yates

A few weeks ago on a Friday afternoon, half an hour after the end of lessons, I cycled from the state school I teach at in Hayes to my old school, St Paul’s in Barnes, to give a talk.

The journey gave me the chance to think about a Institute for Fiscal Studies report published earlier in the day that detailed the growing gap between per-pupil funding in state and private schools.

What, I wondered, would such a gap look like in practice?

It didn’t take me long to see for myself. Upon arrival, I was ushered to a brand-new lecture facility that also incorporates the school chapel, complete with chamber organ (yes, really) and benches bearing the school crest.

This, I came to understand, was all part of the school’s long-term redevelopment project, which got mixed reviews from some of the boys after the talk: ‘It’s a pity that the new Atrium’s so much smaller’, remarked one, ‘and that they didn’t manage to build that nice cylindrical library in the quad.’

‘Yes,’ added another, ‘and I don’t understand why they didn’t build a bigger changing room: we’re stuck changing in two of the three pavilions at opposite ends of the fields. The new canteen is too small as well – they’re having to put extra seats in the fencing salle.’

Before anyone strings me up for guerrilla class warfare, I should stress that the boys I was talking to were all lovely, kind and thoughtful young men.

The problem was that they were completely oblivious to the current schooling reality for 93 per cent of the population.

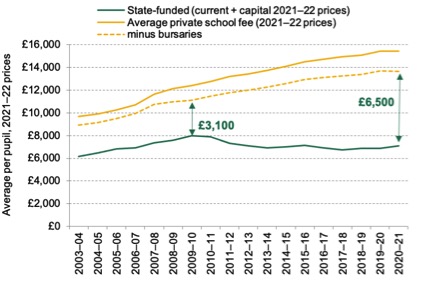

The IFS’s report makes it clear that since 2009-10, net private school fees have risen by 23 per cent in real terms, but spending per pupil in state schools has dropped by nine per cent in real terms.

This widening of the gap between state and private schools means that per-pupil funding in private schools is now 90 per cent higher than it is in state schools.

At sixth form, the funding gap is even larger. So my year 13 tutees chasing places for Oxbridge and medicine are up against some very well-funded competition.

As I cycled home, my thoughts turned to the language used by Boris Johnson and the new education secretary Nadhim Zahawi to describe the government’s vision for education earlier in the week.

Keir Starmer spent a chunk of his Labour conference keynote speech pledging to revoke charity status for private schools, thereby closing a tax loophole and raising funds for access to computers for state school children.

But the only way in which education was married to the Tories’ ‘levelling up’ soundbite was in Johnson’s rehashed promise to send the ‘best maths and science teachers to the places that need them most’.

The juxtaposition of the IFS’s report with Johnson’s public-schoolboy bluster might be funny if it weren’t so galling.

The truth is that any promise to ‘level up’ education in the state sector looks utterly disingenuous.

On the one hand, the government has belatedly accepted the need for countercyclical spending in some areas. This is clear from the furlough policies and business rates relief of the last eighteen months.

On the other, continued tax indulgence of private schools while pursuing a woefully underfunded state school catch-up plan looks like a wilful failure to address a widening gap between the haves and the have-nots.

The government has trumpeted its commitment to the biggest boost to school funding in a decade while hoping that teachers will overlook their culpability for that initial loss in funding during austerity and continued cuts by stealth, both to school funding and teacher pay.

The depressing thing is that after 18 months of trying to teach during a pandemic, we teachers don’t have the energy to call them out.

If you want to level up, don’t make cultural capital a mainstay of the curriculum after closing thousands of public libraries.

If you want to level up, don’t highlight ‘poor and disruptive behaviour’ and then threaten to leave pupils unfed both at home and at school.

If you want to level up, don’t use a school more selective than Oxbridge as your model for all others.

If you want to level up, don’t mandate the teaching of tolerance as ‘British values’ and then choose a social mobility tsar who doesn’t believe in teaching white privilege.

But above all, if you want to level up, don’t continue to make life easier for private school students, who already have so much, while taking away the little that state schools are clinging on to.

Will Yates is a whole-school raising standards officer for gifted and more able students at a community school in west London. He also writes about access to higher education and reducing the gap between the independent and maintained sectors for Times Educational Supplement and other platforms.