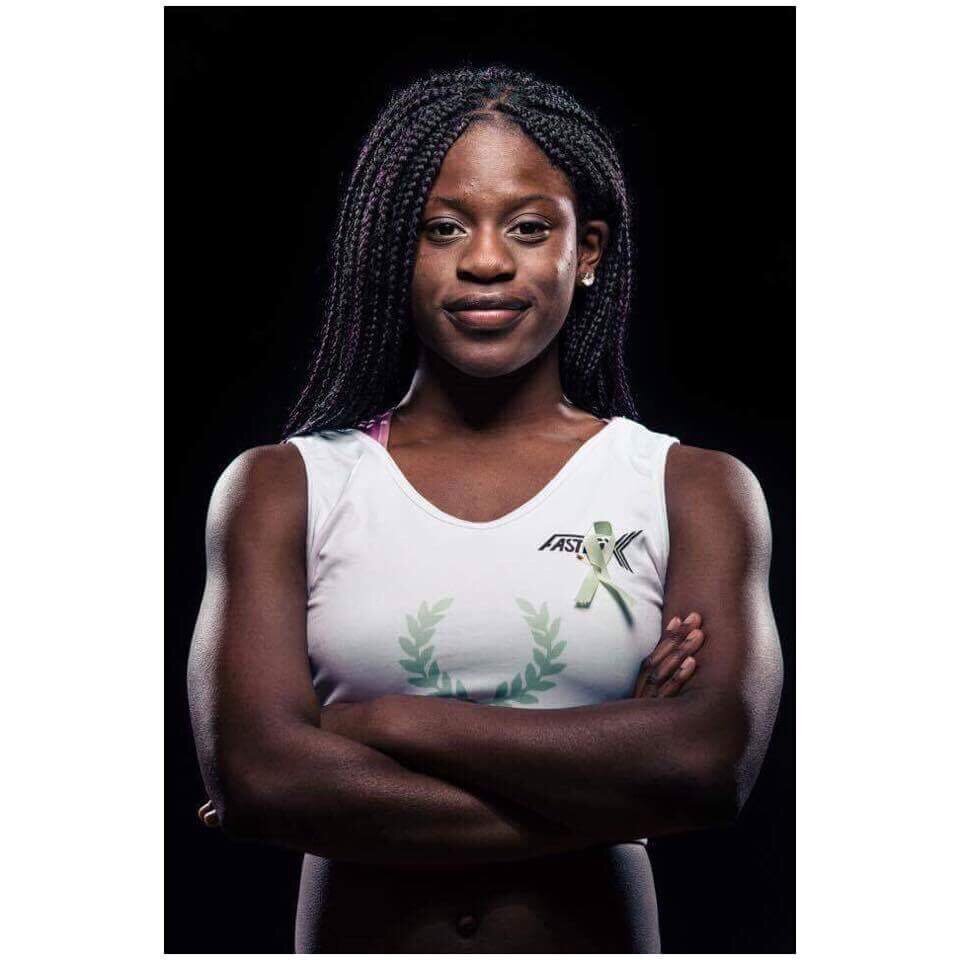

Tiwa Adebayo

The events of the last few weeks have forced many young Black Brits such as myself into a period of intense self-reflection.

Traumatic memories of racist abuse buried deep in our subconscious have once again surfaced and for many this has been truly overwhelming.

A number of our earliest memories of racism took place within an educational context.

Though these problems are severe across the British educational spectrum, it seems that racism is particularly pertinent in and amongst the private sector.

This conversation is a complicated one. As Black private school students and alumni, we remain acutely aware of our inherent privilege whilst struggling to reconcile this with at times, deeply troubling experiences of discrimination.

One former student said “you feel guilty for not enjoying school because you see how much your parents are working and you’re aware that you are more privileged than 90-95 per cent of other people in this country that look like you”.

But the stories of racial discrimination within private schools are stark.

To name but a few: “experiencing countless uses of the n-word by staff and students alike”, having “school teachers, house mistresses and students make derogatory, ignorant remarks”, being called “a black monkey” by a fellow student and having your “combination of blackness and Islamic belief referred to as an “unfortunate mishap, that shouldn’t happen.””.

United by our experiences of racism, last week a group of over 200 Black private school students and alumni came together to speak out about the prevalence of racism in some of Britain’s most elite schools, in the hopes of improving things for those to come.

Our open letter in The Independent details some basic suggestions to safeguard black students and tackle unconscious biases within the staff and pupil populations but in order to achieve real change, it’s clear that a much larger cultural shift is needed.

Having collated over 250 experiences of racism in private schools across the country, one thing is apparent. These aren’t just isolated incidents but in fact symptoms of a wider culture of casual racism and its acceptance that is endemic within the independent sector.

Already, a week since the letter’s publication, hurdles in the quest for change have become apparent.

One barrier is the tendency for private schools to view criticism as a threat to reputation rather than an opportunity for change.

Many emails from students and alumni have been met with replies from the director of communications along with empty statements and social media posts about how the school ‘values its diverse environment and tolerant ethos”.

Until these schools stop attempting damage control and instead actually listen to and acknowledge the experiences of black students, nothing will change.

One school in particular released a statement claiming that they were ‘actively listening’ to their black students and alumni.

But in actual fact, this school had failed to reply to the many emails that had already been sent to them.

This outward facing, performative allyship is simply a quick fix solution, designed to appease and distract others from the deep rooted issues at hand.

Most of these institutions need to go back to the drawing board entirely when it comes to diversity.

There are issues to be addressed in staff recruitment, training and the curriculum to name just a few. Ignoring the problem and offering only words in support is not enough.

Another problem is the lack of one centralised governing body through which structural changes can be implemented.

My inbox is overflowing with correspondences between myself and at least four different independent school trade bodies all with differing membership and objectives. I almost want to ask for ‘the manager’ but of course such a position does not exist.

With the ample liberty afforded to private schools in the absence of the same level of government regulation as the state sector, it seems there isn’t currently a way to enact policy changes from the top down, a necessary mechanism for ensuring lasting change.

Finally, in no way should the onus be on black students and alumni to contribute free labour towards solving problems which are not their own.

Yet if these individuals are not involved in the process the schools will get it wrong.

One solution I’ve suggested to schools is the use of professional diversity and inclusion consultants. Not only will this lift the burden placed on black students and alumni but it will also ensure that these changes are taken seriously and any commitments are honoured.

Whilst any debate about the intricacies of the independent sector is likely to be met with dismissal given the small percentage of pupils affected and the obvious privilege of those involved, I hope that the seriousness of this matter is not overlooked.

I think we can all agree that these are experiences which no pupil should have to endure.

This piece was joint published with The Independent.

Tiwa Adebayo is a graduate in Theology from the University of Cambridge and alumna of Haberdashers’ Aske’s School for Girls (2016). Since graduation she has been working as a communications consultant in Brussels before returning to the UK to continue her career in communications at a London agency. Aside from her day job she is also a freelance journalist writing for a number of publications on subjects such as race, sports and religion.