Tom Fryer

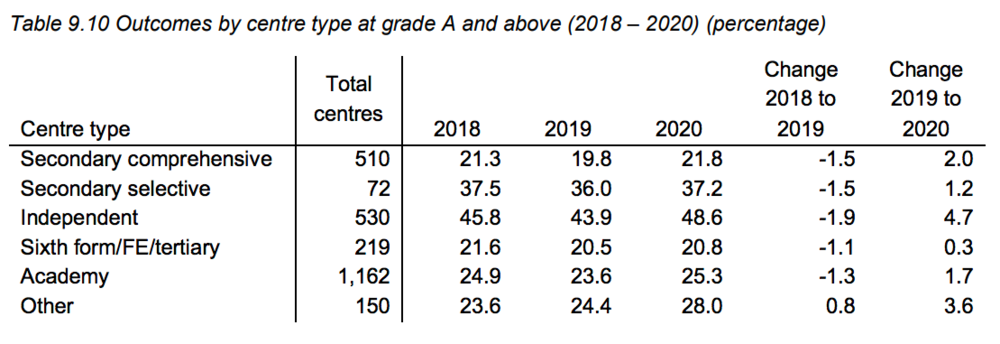

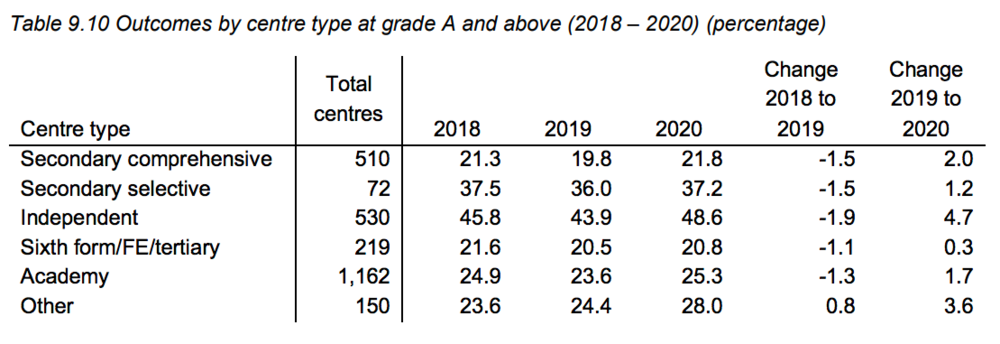

Before it fades from all our memories, allow me to remind you of the infamous Table 9.10 which made its way around Twitter in the wake of the A-level debacle this summer.

It showed that Ofqual’s now-abandoned grade distribution process had disproportionately benefitted independent schools, with a 4.7 per cent inflation in A and A* grades—much higher than increases in the state sector. Take a look below.

However, this misses the most important lesson.

Don’t get me wrong, Ofqual’s proposed process did disproportionately benefit independent schools, and there was plenty of reason to be angry about this.

But, if it’s legitimate to be angry about 4.7 per cent, we should have been fuming about inequalities that are four to five times larger. Let me explain.

Table 9.10 shows that in 2019 when students actually sat exams, independent schools gained 24.1 per cent more A and A* grades than secondary comprehensives, 23.4 per cent more than sixth forms and colleges, and 20.3 per cent more than academies.

That means independent schools got over double the number of top grades compared with comprehensives and sixth forms. This more permanent situation – Covid or no Covid – is something we should really care about.

For all the passionate pleas emerging this August that “the school you go to shouldn’t influence your grades”, it’s important to recognise that this isn’t new.

The school you go to has always influenced your grades.

Think about it this way. Sitting exams is a bit like taking part in a 100m race. Some students look out from the starting line and see a clear racetrack.

Others see a series of pretty imposing hurdles. In non-Covid times, we force everyone to run the race, giving them their finishing time, celebrating the winners of this ‘meritocracy’ and largely ignoring the fact that some ran 100m and others 100m hurdles.

This year, the only difference was that students weren’t able to run the race—they weren’t given their normal chance to stumble and fall.

Sure, Ofqual had a botched attempt at simulating what would have happened in the race, but they didn’t invent the hurdles or the competitive environment. We only have our education system to blame for that.

The key lesson from this debacle isn’t related to statistical models or the effectiveness of regulatory bodies.

It’s recognising that our education system operates as a sham meritocracy, which we’ve allowed to play out year after year, reproducing the very same inequalities.

So, what could we do to change things?

There’s lots of talk about grammar and private schools, but frustratingly universities are less likely to feature in debates about educational inequality.

To be a tad provocative, I reckon if we don’t reform higher education then any changes earlier in the education system will fail.

If you want to change the culture of our educational system, you need to cut the head off the snake.

As long as our universities are characterised by hierarchy and selectivity, there will always be an incentive to seek out competitive advantages at earlier levels of education, often at the expense of real learning.

One exciting idea for reform is a comprehensive university system. This is a system where academic selection has been abolished, meaning that the doors of our universities are open to any members of the public with a desire to learn.

Instead of forcing students to compete to gain access, all universities would adopt the same minimum entry requirements that reflect the actual skills needed to participate on a course.

This means students would be free to apply for the right course, in the right location, and any excess demand would be managed through a lottery system.

In some senses, this change isn’t as drastic as it may first appear. Libraries won’t suddenly start burning their books and great lecture series won’t disappear overnight.

Plus, remember that universities do change—it was only 50 years ago that women were unable to access some institutions.

In another sense, a comprehensive university system would be a big shift. The core purpose of higher education would change from a system structured to sort the wheat from the chaff, to one that tries to provide transformational learning opportunities for everyone across all of their lives.

This comprehensive university system wouldn’t just be more equitable, it has the potential to be better.

Professor Tim Blackman, the vice-chancellor of The Open University, summarised these benefits in his 2017 report for Higher Education Policy Institute.

To take just one example, there is some evidence that diverse environments tend to encourage better learning and communication.

You might not agree that a comprehensive university system is the way forward, but it has to be on the table. It has the potential to shift the purpose of higher education towards transformational lifelong learning for a healthier democracy.

Similarly, by abolishing hyper-selective entry requirements, it could help lessen the competition and inequality at earlier stages of education—why spend huge sums of money sending your child to an elite independent school if this won’t help them access higher education?

It’s not a silver-bullet, but a comprehensive university system could be a vital part of tackling the inequalities shown in Table 9.10.

Moving forward, we need to ask ourselves two key questions:

-

What are the goals of our education system?

-

And, how can we structure our system in a way that best achieves these goals?

Until these questions are on the table, and take the higher education system into account, all other efforts will fail.

For more on comprehensive universities, and other ideas for how to reform universities, check out my short, slightly irreverent and free-to-access publication Naff: Universities and how to change them.

Tom Fryer is a PhD researcher at University of Manchester, a school governor and former teacher.

Why spend huge sums of money on private education? In a large number of cases it is so children can still access high quality co curricular activities such as sport and the arts. These are fields being eroded from state school through chronic underfunding and the dominance of the E-Bacc or Progress 8